I have always been what I call a “nester.” I like my room or my home to feed my aesthetic senses. For example, some artists live in a spare, messy, cave-like environment. But I need beautiful surroundings to feed my soul.

When I was about 16, my father finished off a spare room on the third floor of our Victorian house. He built a closet and a raised bed along the wall with the slanted ceiling, using his signature material, plywood. The bed had drawers beneath and a curtain to close it off from the room. A romantic nest indeed for a teenaged girl. Along the wall to the left, he built a desk; and next to it, under the sole window, a window seat with storage under the lid. I got to choose the color scheme.

I stained the knotty pine plywood a rich red-brown mahogany, a color I still love today. The walls I painted green, still my favorite color. Although in this case the Kelly green I selected became rather strident once the whole room was painted. I had also selected a fabric for the curtains and window seat cushion, pale green with stylized modernistic trees. Alas, as is so often the case, when I went to buy it, it had been discontinued. I had to settle for some old beige curtains with green and pink cabbage roses. Nevertheless, I loved my aerie.

I stained the knotty pine plywood a rich red-brown mahogany, a color I still love today. The walls I painted green, still my favorite color. Although in this case the Kelly green I selected became rather strident once the whole room was painted. I had also selected a fabric for the curtains and window seat cushion, pale green with stylized modernistic trees. Alas, as is so often the case, when I went to buy it, it had been discontinued. I had to settle for some old beige curtains with green and pink cabbage roses. Nevertheless, I loved my aerie.

I had learned this nesting instinct from my mother. She was always buying furniture and décor to create a pleasing environment in spite of her limited finances. In Pennsylvania, the living room had been hunter green with white woodwork. The oak furniture, which she stated had “clean lines,” had been painted flat black. An old library table with curved legs had been cut down to coffee table height and also painted black. That was her “modern period.”

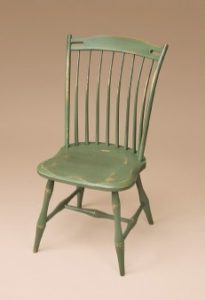

When we moved to into the old victorian in Hingham, she soon embraced the colonial period. Soon the windows were festooned with ancient glass bottles, turned pale green and lavender over the years. A large pickle crock, which I still have, wrought iron cricket boot-pullers, and a copper washing tub crouched near the fireplace. With the help of an antique-dealer friend, she acquired long, narrow, drop-leaf harvest table and four matching thumb-backed chairs that she squeezed into a small room off the living room for dining. I think the chairs were left over from the Spanish Inquisition.

When we moved to into the old victorian in Hingham, she soon embraced the colonial period. Soon the windows were festooned with ancient glass bottles, turned pale green and lavender over the years. A large pickle crock, which I still have, wrought iron cricket boot-pullers, and a copper washing tub crouched near the fireplace. With the help of an antique-dealer friend, she acquired long, narrow, drop-leaf harvest table and four matching thumb-backed chairs that she squeezed into a small room off the living room for dining. I think the chairs were left over from the Spanish Inquisition.

It’s a shame about the chairs, really. When Bob and I moved into our first apartment, my mother gave them to me. Uncomfortable though they were, we needed something. Many years later, when I had one of my once-a-decade fits about cleaning out the attic, I took them to a local antique dealer who only gave me $25 for each. I mean, these were real antiques. They were a matched set, hand-painted. The seats were carved from a solid piece of pine. My mother had always told me they were valuable. I should have taken them down to Hingham where antiques of that vintage were more appreciated. A few months later I spotted them waiting in line on the Antiques Road Show. They didn’t feature them; maybe they really weren’t worth a lot after all. I’ll never know.

Time passed. She added several dry sinks (placed in the bedroom for washing up before indoor plumbing) and had the lovely ceramic bowls and matching pitchers that had adorned them. There were also cherry and chestnut antique chests of drawers. We had a huge old, rather awkward-looking chest of drawers allegedly made by a great-grandfather in Pennsylvania. A love seat and matching side chairs with lovely curved cherrywood legs and arms. After a while, one had to walk sideways to get through the house. The furniture just kept on coming. When my parents moved to their final abode, the central section of an really old colonial built in the 1700s, the furniture spilled over into an old carriage house nearby that was owned by the landlord.

Now this was a pretty big apartment — bigger than my current house. Upstairs it had three generously sized bedrooms, two with fireplaces, and two full bathrooms, one large enough to accommodate a dry sink and a marble-topped chest to hold linens and the TV. Downstairs it had a narrow entrance foyer with a captain’s staircase: a narrow-treaded central section that split left and right half way up and ended in a windowed platform at the top. The foyer had chests of drawers on both sides and a coat tree. To the left and right were two large rooms, also with fireplaces; the one on the right was the dining room. In the rear was a large room paneled in very dark, very wide, ancient pine boards. One wall was dominated by a vast walk-in fireplace with seats inside, left and right, and a beehive oven. A large wrought iron crane carried antique wrought iron kettles. The hearth had antique wrought irons, boot pullers, old earthen jugs, etc. There was also a half bath, a pantry, and a one-story kitchen wing tacked on to the back. This place could hold a lot of furniture!

Let me describe the dining room in particular to give you a flavor of the furniture compulsion. It was about 15 feet by 15 feet, so pretty big. It had a mahogany table with eight chairs, two low antique chests of drawers with mirrors above, a large low oak breakfront (affectionately called “the monster”) and a mahogany glass-topped bar festooned with liquor bottles and glasses. Oh, and also two large over-stuffed club chairs large enough to swallow a six-foot man. This was the main passage way from the driveway in front to the kitchen that jutted out from the back. One had to edge one’s way through the maze with grocery bags in tow.

I sometimes wondered if my mother’s drive to acquire things was a deep response to the impermanence of her childhood. Her father died when she was ten and not long after, her mother went to work as a licensed practical nurse at a county hospital, where she had to “live in.” My mother had to live with one grandmother in the winter and the other grandmother in the summer. Then one of the grandmothers died, and she had to move in with her aunt’s dysfunctional family. But this is just speculation.

For my mother, furniture was an investment. She always bought at auctions and second-hand or antique shops. These were good pieces, solidly built with clean lines — pieces that would last. Much better than the pieces one could buy today in furniture store. These were pieces to be passed down through the generations. When I married, I took quite a few pieces, most of which I am still using: The sectional sofa in the living room, the central section of which is in the attic, several antique chests, one with a marble top, a drop-leaf mahogany table stuffed into a corner, and a small upholstered chair with fluted legs.

I have encountered this same “furniture for the ages” ethic among my “old money” friends, but at a much more exalted level. Many of them have magnificent, sometimes rather worn, oriental rugs passed down through many generations. Their chests of drawers are museum-quality pieces. Their leather chairs show the patina of use. When you walk into a room like that, usually with white walls and curtains, oil paintings on the walls, and canton china in the bookcases, it exudes a sense of calm, warmth, and comfort.

Later, I passed some furniture on to my son Curtis when he moved to California: the six of black-painted dining room chairs and a huge dark chest of drawers from my sister Chris’s in-laws. (Those giant “man’s chests” are hard to find.) When he decided to move onto a boat to live, he gave them all away. I was scandalized. Apparently I had not passed on the family furniture ethic.

When my mother finally moved into my sister Chris’s house after my father died, she had to find good homes for all her stuff. My sister Beverly took my grandmother Wright’s little “ladies desk” and several glass curio cabinets and dry sinks. Chris’s house was the only one large enough to hold the club chairs. Chris also had the cherry-armed loveseat and matching chairs restored and found places for them in her home. I had space for only a few things. While my house is not as stuffed as my mother’s, there’s not a patch of wall that lacks a table or a chest of drawers. I do try to keep the center open (somewhat).

Recently I decided to replace the rug in my dining room. It was warn to the beige backing in many places. It had lived in my mother’s dining room for 30 years, then lived in mine for another 20 or so. It was a machine-made wool Belgian rug, but I loved it. It was a pale teal blue, oriental style, with touches of ivory, salmon, and pale green. When I originally decided I could afford to buy a rug for my dining room, I had gone from store to store, looking for a rug but finding nothing that seemed right. Then I went to visit my mother, spotted her rug, and realized that that is what I had been seeking; it had been imprinted on my mind. I found and bought a duplicate. When that wore out, I inherited hers. But now it had lived its life and I needed a new one.

In the tradition of buying for the ages, I went to an Oriental rug place in Acton that was going out of business. I looked at every rug they had in my size range. The cheapest were about $3,500, but I didn’t like them much. The one I loved cost $32,000 (I have always had good taste!). “Hey,” I told the proprietor, “I could buy a Prius for that!” Then I went up the road to a regular rug store. They had several machine-made rugs that I really liked, and they were much cheaper. I struggled with my “buy for the ages” ethic. After all, who would ever want my rugs? My son Curtis’s wife has asthma that is exacerbated by rugs, so no rugs for them. My son Eric lives in a condo with wall-to-wall carpet. He couldn’t care less about Orientals. So I broke free. These rugs are for me, not the generations, and I really like them. The colors sing to me and harmonize with the rest of my furnishings. They only need to last another 15 years or so.

Now that I have broken free, perhaps I will replace the small chair from my mother with a big comfortable chair for my largish husband. He says he slides out of all our chairs; they probably aren’t deep enough for his long legs. Maybe I’ll really go wild and go to a furniture store. But more likely I will look at “Tables to Teapots” for a nice second hand chair. After all, they don’t make furniture as well as they used to.

Leave a Reply